Goldilocks' Variable

![[Discovery images]](../../Pics/Leos/glcompare.jpg) One of the most exciting times of my life followed after I realized that

a reddish star easily visible on the cover of the June 1990 issue

of Astronomy was completely

lacking on the cover of the Autumn 1990 issue of Deep Sky which,

by a remarkable coincidence, showed apparently the same Dumbbell

nebula (M27, NGC 6853). Reproduced by permission. Copyright © 1990,

Kalmbach Publishing Company.

One of the most exciting times of my life followed after I realized that

a reddish star easily visible on the cover of the June 1990 issue

of Astronomy was completely

lacking on the cover of the Autumn 1990 issue of Deep Sky which,

by a remarkable coincidence, showed apparently the same Dumbbell

nebula (M27, NGC 6853). Reproduced by permission. Copyright © 1990,

Kalmbach Publishing Company.

To put it lenghtily, all that began a long time ago, well before

the Internet entered my life. Getting

acquitanced with the fascinating world of planetary nebulae, I found,

much to my surprise, that many of them had their stellar nucleus

double. A popular book on astronomy (I can't recall its title now)

even said that also the brightest planetary, the Dumbbell nebula

(M27, NGC 6853) belonged to the class. Unfortunately,

as it is often with similar sources, no reference or authority was

given, and I forgot the episode.

A couple of years later I used to make regular trips to the library

of the Astronomical Institute

in Ondrejov, a quiet village in a

nice hilly landscape some 30 kilometers from Prague, with forests all

around and great beer in local pubs. By that time I had

already learned to read technical papers and now I got access to the

large library full of goodies! Browsing through bibliography of

planetary nebulae in hefty volumes of Astronomy and Astrophysics

Abstracts, I came across a paper "A probable binary central

star in the planetary nebula NGC 6853" (PASP 89, 139,

1977) by Kyle M. Cudworth of the

Yerkes Observatory.

Comparing positions of a 17th magnitude star next

to the nebula's nucleus (separation 6.5", position angle 214deg)

measured at Lick and Yerkes plates in the 1960s and 1970s, he found that

both the stars moved together and suggested they could be physically

related to each other.

|

|

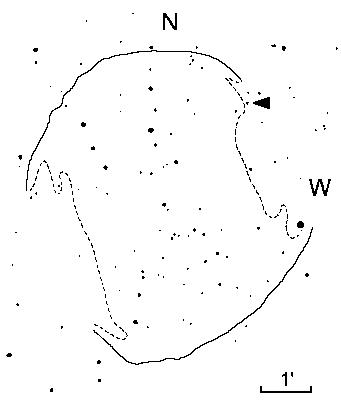

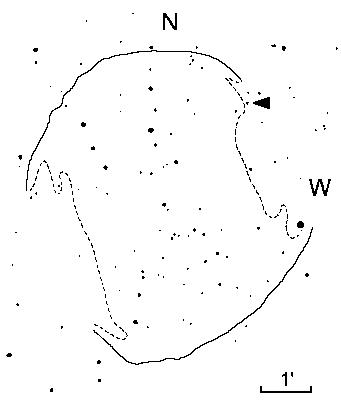

Finding chart for Goldilocks' variable (arrowed). The common-proper-motion

companion of the stellar nucleus is a small star next to (and southwest of)

the latter.

|

I knew that binarity of some other planetary nebulae was much more

dramatic (as it is with

V 651 Mon, the unique nucleus of NGC 2346), but this was

a little known detail I could add to a picture of a well-known object.

Having realized that the common-proper-motion companion was visible on

many published pictures of the summer planetary, I decided to

prepare a map which would show the

nebula's extent in various colors (and the light of various ions)

and also that pair of the stars. Hoping, of course, that I would find

other interesting features to be marked on the chart. I took June 1990

issue of Astronomy with a beautiful blue-red bubble of the

Dumbbell (captured with the Canada-France-Hawaii

Telescope) on its cover, and started plotting

the star field on a tracing paper. To check my creation I reach for

the Autumn 1990 cover of Deep Sky which, by a remarkable

coincidence,

showed apparently the same Dumbbell, with similar orientation and

scale. I corrected position of a few small stars when I got to the

northwestern corner of the nebula and became puzzled. The place

occupied on the cover of Astronomy by an easily visible reddish star

was quite empty on the Deep Sky picture! I had never heard

about a variable star in

M 27 so I began eagerly chasing after photographs of

the planetary.

When I emerged from books and journals heaped up during the search,

I was sure that the star was really a variable, not an artifact due

to some misprint, different magnitude limit or color sensitivity.

I was looking forward to add to my chart a detail completely

forgotten by authors of deep-sky guidebooks, but first I had to find its

coordinates to check them against variable star lists. First aid was

given by the image of M27 reproduced in Perek & Kohoutek's

Catalogue of Galactic Planetary Nebulae, the only

source at my disposal with clear orientation, angular scale and

coordinates of the stellar nucleus. During my next visit at the

Department of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, Masaryk

University, Brno, I went through the General Catalogue of Variable

stars (GCVS) that listed variable stars known in early 1980's, as

well as its more recent supplements. But none of those authoritative sources

mentioned the star of the Astronomy cover! I determined the

position again allowing for a pessimistically large error, checked

the latest numbers of

IBVS

(Information Bulletin of Variable

Stars), but the result was the same. Finally, I admitted

the star was a discovery, and sent a short announcement

to IBVS through Attila Mizser

(Konkoly Observatory).

An enjoyable response - a small card saying that the

contribution was accepted and would appear in #3604 -

came within a few days.

|

|

|

It required 24 individual exposures of six fields to create this

CCD mosaic of the Dumbbell Nebula. Daniel Del Rio (Fort Lauderdale,

Florida) took them on November 23, 1994, with a ST-5 camera attached at

his 14.5-inch reflector.

|

That happened in the spring of 1991. What is known about the variable

today, six years later? The most precise piece of information is its position.

Soon after the discovery, Jan Manek (Stefanik Observatory, Prague) found that

my original coordinates were erroneous. Applying standard astrometric procedures to

a pair of photographs of the Dumbbell which appeared in print, he derived

new declination and right ascension:

19 h 59 m 29.8 s, +22d 45' 14"

(2000.0, precessed from the original 1950.0 equinox using the NED online

calculator). However strange his method may seem, it worked surprisingly well.

In the summer of 1992, Petr Pravec (Astronomical Institute, Ondrejov) took at my

request several CCD frames of the planetary nebula and measured them with the

following result: 19 h 59 m 29.7 s, +22d 45' 12" (2000.0).

The third (and so far the last) position I am aware of is that published

by M. Morel (Rankin Park, Australia) in the IBVS #4037 (Improved

Astrometry for Variable Stars): 19 h 59 m 29.8 s,

+22d 45' 13" (2000.0). As you can see, the three sets of coordinates

agree perfectly with each other, given that the first one is based on

the SAO catalog and the others on the GSC data.

Unfortunately, situation with the variable's photometry is much worse.

It seems most likely that it belongs to the class of long-term variables of which Mira

(Omicron Ceti) is the most popular representative. This is indicated by the

red color of the star, the reason it's so bright on frames taken by common

CCD cameras and on the near-infrared image of the Dumbbell nebula reproduced

in the September 1996 issue of the Sky & Telescope, page 16.

More importantly, the classification is supported by character of light changes

documented by a series of CCD frames made by Daniel Del Rio (Fort Lauderdale,

Florida) during the fall of 1994. Using the ST-5 camera attached at his 14.5-inch

Newtonian, he got so far the best brightness measurements. Alhough relative and unfiltered,

Daniel's photometry show that the variable has brightened by some two magnitudes

between the early October and the late November of that year (the check star nearby was constant

within a few hundredths of magnitude).

This is too much for other sorts of red variables (those various semiregular

and irregular beasts). In addition, the real range may be even greater, because

the images of the variable and comparison star turned out to be saturated.

But that all isn't enough for giving the star (which I privately

named Goldilocks' variable after a ravishing young lady) the

definitive designation V XXX Vul. With Vulpecula the Little

Fox rising again above the morning horizon (now decorated with the comet),

it should be quite easy for an experienced variable star observer equipped

with a CCD camera (and ideally also with the standard R or V filter) to follow

its changes closely thorough a cycle or two. Needless to say, I would

much appreciate any results. Clear skies!

(March 1997)

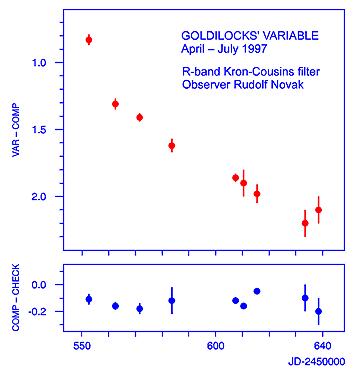

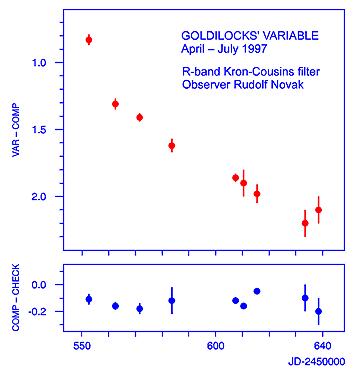

First update

While the comet mentioned above is finally gone, Goldilocks' variable is

still out there, and what is most important, you can enjoy a preliminary

light curve prepared by

Rudolf "Karel" Novak

(Nicholas Copernicus Observatory and Planetarium, Brno).

Between April and early July 1997, he took several frames with a ST-7 CCD

camera (R-band Kron-Cousins filter) attached at the Brno Observatory

40 cm (f/4.4) reflector, and processed them by the MIDAS

aperture photometry function magnitude/circle.

The results are presented in the accompanying diagram. The top panel shows

the magnitude difference between the variable and a comparison star, the

bottom panel the same for the comparison and a check star.

Rudolf's most recent measurements (not included in the diagram yet) indicate

that Goldilocks' variable has already reached its minimum and is brightnening.

(September 1997)

To Attila Mizser (Konkoly Observatory) who arranged publication of

my discovery report in IBVS. To Petr Pravec (Astronomical

Institute, Ondrejov) and Jan Manek (Stefanik Observatory, Prague) for

their careful positional measurements. To Daniel Del Rio for an

envelope full of goodies related to the Dumbbell Nebula and nice CCD

images. To Dave Bruning and Terry Conley (Astronomy) for

permission to reproduce the discovery images. And to Rudolf Novak for

his present and future photometry of my favorite variable star.

Leos Ondra (leo at sky.cz)

October 16, 1998

Hartmut Frommert

Christine Kronberg

[contact]

![[SEDS]](../../Jco/seds1.jpg)

![[MAA]](../../Jco/maa.jpg)

![[Home]](../../Jco/messier.jpg)

![[Back to M27]](../../Jcon/m27.ico.jpg)

Last Modification: February 19, 1999

![[Discovery images]](../../Pics/Leos/glcompare.jpg) One of the most exciting times of my life followed after I realized that

a reddish star easily visible on the cover of the June 1990 issue

of Astronomy was completely

lacking on the cover of the Autumn 1990 issue of Deep Sky which,

by a remarkable coincidence, showed apparently the same Dumbbell

nebula (M27, NGC 6853). Reproduced by permission. Copyright © 1990,

Kalmbach Publishing Company.

One of the most exciting times of my life followed after I realized that

a reddish star easily visible on the cover of the June 1990 issue

of Astronomy was completely

lacking on the cover of the Autumn 1990 issue of Deep Sky which,

by a remarkable coincidence, showed apparently the same Dumbbell

nebula (M27, NGC 6853). Reproduced by permission. Copyright © 1990,

Kalmbach Publishing Company.

![[SEDS]](../../Jco/seds1.jpg)

![[MAA]](../../Jco/maa.jpg)

![[Home]](../../Jco/messier.jpg)

![[Back to M27]](../../Jcon/m27.ico.jpg)